At the intersection of Gravois and Morganford, in the heart of South St Louis City, a sixty foot Dutch windmill rises above the horizon: Bevo Mill. My first teaching job in 2000 was at a small, Catholic high school in this diverse and bustling neighborhood filled with unique architecture and a rich history. Since I didn’t grow up in St Louis, I was fascinated by this unusual building in a vibrant business district in the middle of a working class neighborhood.

Bevo Mill (Photo Credit: https://www.bevocid.com)

August A. Busch, Sr. built Bevo Mill in 1916 at the halfway point between the Anheuser-Busch Brewery and his estate at Grant’s Farm, so he could stop and have a beer during the trip. It served as his family’s private dining hall and a beer garden and restaurant for guests. Prior to building Bevo Mill, Busch had toured Holland for a year to study the architecture of the Dutch windmills in order to recreate an authentic mill in his hometown St Louis. Known as one of his prohibition houses, Busch named the mill after a “temperance drink” that Busch manufactured and distributed around the country. The name of this non-alcoholic malt beverage was Bevo, which stems from the Bohemian word “pivo” for beer. In an interview from December of 1916, Busch spoke about the idea behind his German beer hall:

It is my belief that the ultimate outcome of the prohibition sentiment in this country will be establishment of the German saloon system.

German saloons sell only beer, light wines and temperance drinks. There are no bars and no treating. Many of the evils of drink are attributable to the treating habit. A man goes into a saloon and gets a glass of beer. He meets a friend or a group of friends, and sometimes 20 or 30 drinks are consumed. The treating system ought to be prohibited.

I am spending $124,000 to build a Deutsche wirtschaft at Gravois and Morganford roads to demonstrate that an institution at which only beer, light wine and temperance drinks are served can be made a success. I am going to call this the Bevo Mill. It is to be constructed principally of varicolored stone, most of which with my own hands I gathered from my place, the Grant Farm.

There will be no bar in the establishment. There will be a high class café, which I have engaged Henry Dietz, former chief and manager of Faust's, to conduct for me. All drinks will be served at tables.

Bevo Mill Opening, June 19, 1917 (Photograph by J.R. Eike from the Thomas Kempland Collection)

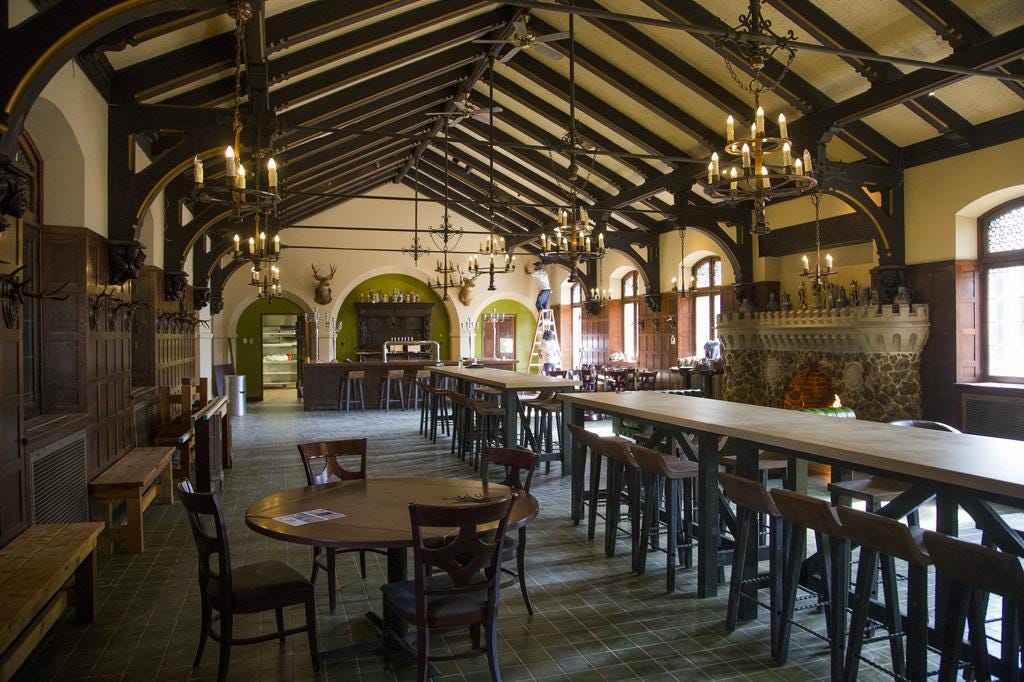

The base of the tower, built from stones that Busch hand-selected from his Grant’s Farm property, was surrounded by a wooden observation deck. On the ground level, there was a restaurant and an outdoor garden. The upper floors consisted of an eight-room apartment and laundry facilities. A Dutch mill expert was brought in to help set up the massive wooden blades, which were driven by a 24-inch-thick shaft extending through a marble bearing. The interior of the mill had an octagonal dining room with hand-carved gnomes, arches, beams, large murals made of painted porcelain tiles, and oak wainscoting. Boar and deer heads were mounted on the walls, and a large fireplace was used to roast chickens.

The main hall at Das Bevo. (Photo Credit: DILIP VISHWANAT|SLBJ)

After prohibition ended, Bevo Mill closed to the public but was available for private parties until 2009 when the Busch family sold the property. After a series of closures, renovations, and changes in ownership and usage, Bevo Mill has recently reopened as Das Bevo, a German-inspired restaurant, beer hall, and event space. Bevo Mill is a distinct landmark in the city of St Louis, and the nearby streets in this neighborhood have also become a destination for food and drink.

The Bevo Mill neighborhood in St Louis has long been a home to immigrants since it was first settled by German mine workers in the 1830s. Beginning in 1950, St Louis City experienced population decline—800,000 residents in 1950 to about 400,000 by 2000. The Bevo neighborhood had a 5% increase in population in the late 1990s and early 2000s when Bosnian refugees settled in the neighborhood, fleeing ethnic cleansing, concentration camps, and a bloody civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. According to The International Institute of St. Louis, the St Louis metropolitan area had about 70,000 Bosnian residents in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Most of the refugees were housed in the Bevo Mill neighborhood because of the availability of housing, and Bevo Mill became unofficially known as “Little Bosnia.” This became the largest population of Bosnians in the United States and the largest Bosnian population outside of Europe.

When I began teaching in 2000 at St John the Baptist Catholic High School, just down the block from Bevo Mill, most of my students were from multi-generation Bevo families, and they only had negative things to say about their new neighbors. They laughed about stealing shoes off of the Bosnian residents’ porches, and they claimed that the Bosnians were roasting and eating dogs. Every once in a while, chickens would wander the halls of the high school because some students thought it would be funny to take them from the Bosnians’ yards during their walk to school. My students were often getting into fist fights with the Bosnian teens on their block, and they told the Bosnians to go back to their own country. The American teens didn’t understand that the Bosnian families had lost their families and homes, and they no longer had a home to return to. My students did not understand the Bosnian War or why these refugees had suddenly moved to their neighborhood in such large numbers. St Louisans were fearful of change. By the early 2000s, my students watched as the hardworking Bosnian families found success in St Louis, driving nicer cars than they did and owning more property and businesses than their families that had lived in Bevo for generations. The native St Louisans in this working class neighborhood were resentful toward their new neighbors. Rather than recognizing the Bosnians’ entrepreneurial spirit and contributions to the city, my students angrily and falsely claimed that the government was giving the Bosnians money, and they believed that the Bosnians didn’t do any work to earn those expensive cars.

According to the International Institute of St Louis, refugees only receive a modest amount of financial assistance during the first 90 days upon arrival, to pay for housing, food, and essentials. They receive very little spending money. For example, a family of 5 receives a total of $60 in spending money for use during those first three months in America. Refugees find that they very quickly need to find work to support themselves. Also, after six months, refugees are required to begin repaying their travel loans, which can be as much as $1500 per person. There are special small business loans available to refugees, but the interest rates are higher than the banks, so refugees are encouraged to save money and build their credit history to seek a traditional business loan. Contrary to what my students had been telling themselves, after their first 90 days in America, their Bosnian neighbors were not receiving free money from the government.

As an outsider and nonresident of this neighborhood, I could only see the immigrants' outstanding contributions to St Louis City. They overcame so much loss as they fled from their homes that had been devastated by war. As they started over in our city, they revitalized a crumbling and deteriorating neighborhood. Numerous Bosnian restaurants, bakeries, clubs, and cafes began filling the abandoned storefronts along Gravois and Morganford, and they saved the neighborhood, bringing it back to life. Over twenty Bosnian businesses opened in Bevo within the first ten years of their arrival to St Louis. In 2001, I visited one of the Bosnian cafes that rarely had American patrons. The simple interior was bright and cheery, and the air was filled with the sounds of the Bosnian language and traditional folk music. My server didn’t speak English, but he was welcoming and served me a thick, black coffee like I had never had before. He eagerly showed me how to properly pour myself a cup.

In an old Pizza Hut, Bosna Gold restaurant opened in 1997 as the first Bosnian-owned business in St Louis. Other Bosnian restaurants began popping up as well: Sarajevo, Sweet P's, Miris Dunja, and Europa Market. A Bosnian-language magazine for new immigrants was published in St Louis from 1997 to 2000, Plima Obiteljski Magazin. The title translates to “Ocean Tide” and was distributed to other cities across the United States. In this era before the internet, the magazine gave advice to newly arrived refugees, as well as pop culture news from the former Yugoslavia. In 2014, the Bosnian community of Bevo was shocked when a violent hammer attack by four teenagers killed a young Bosnian immigrant, Zemir Begic, who was out with his fiancee in the Bevo neighborhood. The next day, hundreds of Bosnians protested in the streets, chanting “Bosnian Lives Matter!” claiming that the police had not done enough to keep the Bosnian community safe. St Louis Mayor Francis Slay responded that there was no evidence that the crime was connected to the race or ethnicity of the victim, and he defended the police and placed the blame on the community. Bosna Gold closed its doors in 2016. Soon, more and more Bosnian businesses followed their lead by moving out of the city. Most Bosnian residents have since moved to the suburbs, seeking bigger homes, better schools, and lower crime rates; few Bosnian residents have remained. Former St. Louis City alderman Antonio French said, “Unfortunately, this huge opportunity we had with this large population of Bosnians living in the city, we have not maximized it. And over the last 20 years, we have lost most of them.”

The Bevo Mill neighborhood of St. Louis, where many Bosnian refugees settled after fleeing war in the Balkans.(Photo Credit: Carolina Hidalgo for The New York Times)

St Louis must shift how we think about immigrants to our city by recognizing the invaluable contributions they have made to our community. It is time to fully embrace and celebrate these new residents who have brought with them unique cultures, traditions, and skills, making our city stronger. The immigrant and refugee communities have infused St Louis with a vibrancy that resonates in our neighborhoods and on our streets by making our community a more dynamic and diverse place for all of its residents. Their resilience and hope should be welcomed by every St Louisan who looks toward the city’s future.

Although the Bevo neighborhood is not as vibrant as it was in the early 2000s, immigrants have continued to settle into the area and have opened new restaurants in the former Bosnian-owned properties along Gravois Avenue. A few Bosnian restaurants, bakeries, and cafes remain. Twenty six years after the first Bosnian-owned business opened in St Louis, I returned to Bevo Mill and visited the new refugee-owned restaurant in the space of the old Bosna Gold restaurant.

Continue Reading: Bevo Mill Part 2–Refugees in Little Bosnia Today

Sources:

https://www.stlbosnians.com/doing-just-fine/

https://losttables.com/bevo/bevo.htm

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/18/us/bosnian-refugees-st-louis-midwest.html

https://www.cnn.com/2014/12/02/us/st-louis-man-killed-hammer-attack/index.html